By Savannah Labbe, 10-24-16

In doing research for my previous post on the U.S. Christian Commission, I came across an intriguing artifact: a Civil War era identification tag, or dog tag. When I picture a military dog tag I see a metal rectangle suspended from a necklace, like those worn by today’s soldiers. One doesn’t usually associate dog tags with the Civil War, which is why I was interested to find one. However, it is not surprising that the basic human fear of dying unknown, of robbing one’s family of closure and certainty, was present during the Civil War just as it is today. This is why there are accounts of Civil War soldiers crudely fashioning their own dog tags before going into battle. At Cold Harbor, soldiers wrote their names and addresses on a piece of paper and pinned them to their uniforms before charging to their deaths during the suicidal attack that occurred at that battle. There are also accounts of soldiers making dog tags out of old coins and pieces of metal and wood. In addition, they would carve their initials into items of clothing or carry around photographs of family members to help ensure their identification.

During the Civil War the government did not have the capacity or the willingness to issue dog tags to every soldier. A request was made to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton to issue a dog tag to every Union Soldier, but it was denied. Thus, soldiers had to look elsewhere for their dog tags, prompting some of them to make or purchase their own. They could buy silver or gold disks with their names stamped on them from the sutlers that followed the army. The U.S. Christian Commission also issued identification tags and distributed approximately 40,000 personal identifiers to Union soldiers.

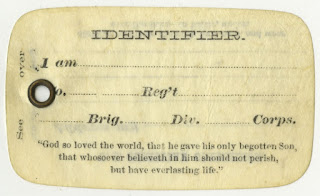

I got a chance to examine one of these identifiers. It was made out of paper with a hole punched in the top surrounded by a metal ring. Soldiers were instructed to hang this piece of paper from their neck with a cord. On the front side there were spots for the soldier’s name, regiment, brigade, division, and corps; on the back there was a place for the soldiers address. In addition, the front read, “God so loved the world that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish but have everlasting life-,” a fitting statement to put on an item that would be most useful after a soldier’s death, a reassurance that the soldier would be able to live on.

The Civil War was the first time it became evident that there was a need for some form of identification tag for soldiers. However, it took a long time for dog tags to become standard issue of the army. During the Spanish-American War a chaplain named Charles C. Pierce pioneered soldier identification techniques. It became practice of the army during this war to temporarily bury its dead and later exhume and identify the bodies, which was Pierce’s duty. He did this by collecting all known information about the casualties–characteristics, place of death, and nature of wounds–then comparing the information with the bodies of the soldiers he exhumed. Using these techniques Pierce was able to identify all the bodies he exhumed while working in the Philippines. He was also one of the first people to suggest that the army should provide aluminum disks with the soldier’s identification information to every soldier.

By the First World War these disks became very common and were made mandatory by the army. The Second World War saw the evolution of the modern rectangular dog tags suspended from metal chains that provided the soldier’s name, service number, blood type, and religion. Now the dog tag has evolved into a wearable flash drive detailing the soldier’s medical information. From its humble beginning as a piece of paper to its latest incarnation, the invention of the dog tag in the Civil War has had a great impact on the ability of the army to identify soldiers’ bodies. The relative rarity of dog tags and unstandardized burial practices in the Civil War made it so 40% of the dead are still unidentified to this day. The dog tag, while a small and seemingly insignificant object, has prevented many soldiers from dying in obscurity, like so many did during the Civil War.

Sources

“DOG TAGS.” Military History 24, no. 7 (October 2007): 13. Accessed September 25, 2016.

Hirrel, Leo P. “The Beginnings of the Quartermaster Graves Registration Service.” Army Sustainment 46, no. 4 (July 2014): 64-67. Accessed September 24, 2016.

McCormick, David. “Inventing military dog tags.” America’s Civil War 25, no. 2 (May 2012): 56-59. Accessed September 24, 2016.

Musil, Melinda. “MOLDED BY WAR.” America’s Civil War 29, no. 3 (July 2016): 40-49. Accessed September 25, 2016.

U.S. Christian Commission Dogtag. Civil War Vertical File Manuscripts. Special Collections/Musselman Library, Gettysburg College, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

Image 1: A Civil War dog tag that would have been issued by the U.S. Christian Commission. Photo credit: Special Collections, Musselman Library.

Image 2: The back of the dog tag. Photo credit: Special Collections, Musselman Library.

From: gettysburgcompiler.com

0 comments:

Post a Comment